https://carnegieendowment.org/

War and Peace: Ukraine’s Impossible Choices

Two years into Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine, a Carnegie-sponsored opinion poll found that Ukrainians still believe strongly in their national cause, even as doubts creep in about the path to victory.

By Nicole Gonik and Eric Ciaramella

Published on June 11, 2024

PROGRAM

Russia and Eurasia

The Russia and Eurasia Program continues Carnegie’s long tradition of independent research on major political, societal, and security trends in and U.S. policy toward a region that has been upended by Russia’s war against Ukraine. Leaders regularly turn to our work for clear-eyed, relevant analyses on the region to inform their policy decisions.

In recent months, Ukraine’s battlefield prospects have seemed some of the bleakest since the early days of the invasion, despite the long-awaited approval of the U.S. aid package.

One would expect that Ukrainian society would have pessimistic assessments of the war’s trajectory. But a Carnegie-sponsored opinion poll conducted in mid-March 2024—just weeks after Ukrainian troops were forced to retreat from Avdiivka and amid heavy Russian bombardment of Ukraine’s energy grid—found the opposite to be true. (The full results of the poll, conducted by the Rating Group, are available here. See box for survey methodology.)

Ukrainians overwhelmingly rejected the notion that Russia is winning the war (only 5 percent believe it is); the remaining majority was split almost evenly between those who thought Ukraine is winning and those who thought neither side is winning. When it comes to war outcomes, 73 percent of Ukrainians believed that Ukraine will eventually liberate all of its territories. A sizeable percentage also believed that Ukraine will regain some or all of its territories within the next year (56 percent) and that the war will end within two years (59 percent). While other polls have found less optimism about the current situation, the general belief in eventual victory is consistent across recent polls.

For President Volodymyr Zelensky, Ukrainian society’s resilience and optimism are both an asset and a liability. Russia’s attempts to force Ukrainians to capitulate to its demands have clearly failed. Zelensky can credibly argue to Ukraine’s partners that his war strategy has widespread domestic support.

At the same time, Ukrainians’ high expectations create the potential for widespread disappointment if the war culminates in an outcome short of total battlefield victory and territorial liberation.

As he struggles with a precarious situation on the front and tough decisions about a further mobilization of troops, Zelensky will have to balance between bolstering society’s morale and offering realistic assessments of what can be achieved.

Survey Design

The data analyzed here are based on a survey of 2,000 Ukrainian adults from all regions of Ukraine, except for the temporarily occupied territories of Crimea and Donbas and territories lacking Ukrainian cellular coverage at the time of the survey. The survey was conducted via computer-assisted telephone interviewing and the results were weighted by age, sex, and type of settlement (urban versus rural) to ensure a representative sample. The survey was designed by scholars at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and was conducted by the Ukrainian sociological organization Rating Group from March 7–10, 2024. Overall results have a margin of error of plus or minus 2.2 percent; the margin of error for individual demographic sub-categories is higher.

The Generational Divide

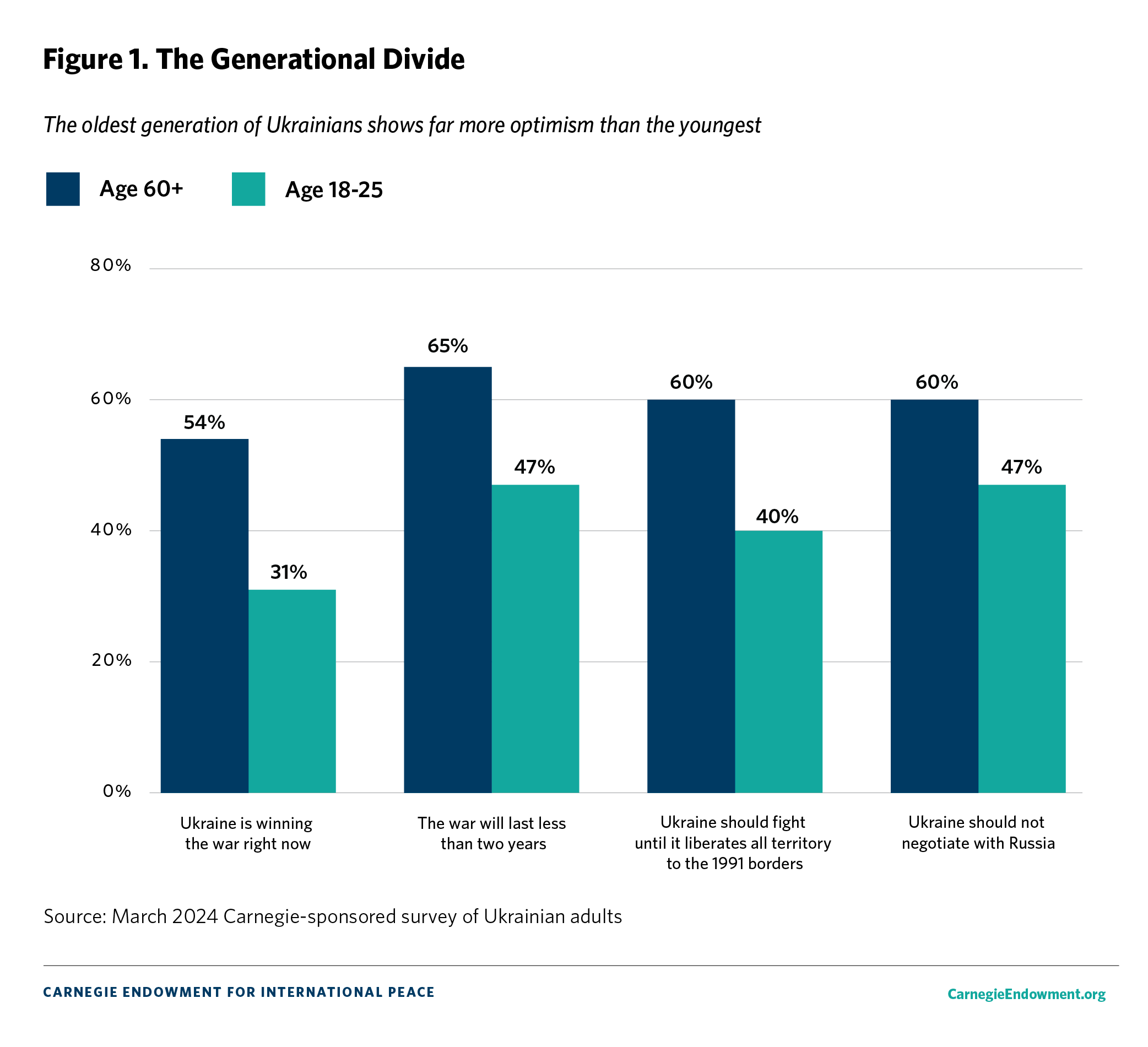

The poll results showed a chasm between older and younger generations of Ukrainians about assessments of the war’s trajectory and about policy preferences (see figure 1). Older Ukrainians, aged sixty and above, stand out for their war optimism across virtually every metric. This group had a rosier assessment of current battlefield dynamics and was more confident in eventual Ukrainian victory, more inclined to believe that the war will end soon, most supportive of continuing to fight until all territory has been liberated, and largely opposed to negotiating with Russia.

This optimism among older Ukrainians is consistent with results from other recent polls, such as the National Survey of Ukraine conducted in late February. But it challenges conventional wisdom about societal attitudes. Older Ukrainians have the most experience living under Soviet rule, and it may be intuitive to think that this generation is more likely to accept the idea of cultural, linguistic, and historical ties to Russia (which is not, of course, the same as having pro-Russia views). Other polls from the past two years have shown hints of this phenomenon: the oldest generation is least likely to support removing the Russian language from official communications in Ukraine, is most likely to identify as citizens of the former Soviet Union, and is most likely to believe that Ukraine and Russia used to be “brotherly nations.” In polling prior to the full-scale invasion but after the annexation of Crimea in 2014, the oldest generation was least likely to believe that there was a war going on at all.

In contrast, younger Ukrainians, especially those under thirty-five, tended to be most pessimistic about Ukraine’s prospects for victory and most willing to accept limited war outcomes. Only 40 percent of those aged eighteen to twenty-five thought that Ukraine should fight until it liberates all of its territory to the borders established on Ukraine’s independence in 1991, compared to 60 percent of those sixty and older. On the surface, these results may seem surprising. Other polls have shown young Ukrainians being more optimistic about Ukraine’s prospects in the long term. And over the past decade, younger Ukrainians have been at the forefront of demanding that their leaders reform the country and move it toward Europe.

But there is a reason that younger Ukrainians are more anxious about the war than their elders: they are the ones who will have to fight it.

Support for further mobilization across age categories illustrates this point: 72 percent of Ukrainians over age sixty supported further mobilization, whereas opinions were evenly divided among those under forty-five. The latter group, of course, is more likely to be drafted. Younger Ukrainians probably also see the war upending their lives, affecting everything from their job prospects to their decisions about whether and when to start a family or whether to remain in Ukraine.

Another possible explanation for this generational divide lies in the differing information sources used by the oldest and youngest Ukrainians. Polls show that older Ukrainians are far likelier to receive their information about the war through the government-curated United News telethon, as opposed to Telegram or YouTube (more favored by the youth). The telethon, which Ukrainians have been steadily losing trust in, has faced critique for its content being “censored, embellished or presented in an overly patriotic way” (author’s translation). Ukrainians have cited this as a reason for their falling trust in it as a source, and Ukrainian media experts have described the telethon as overly optimistic or even as “state propaganda.”

One final category of respondents deserves special mention: veterans and active-duty soldiers. Whereas older Ukrainians were optimistic and determined and younger Ukrainians were pessimistic and cautious, those who have served in the Ukrainian Armed Forces were pessimistic but determined.

They were least likely to believe that Ukraine is winning the war (32 percent) and least likely to believe that the war will end in less than two years (50 percent). At the same time, they were more likely to believe that Ukraine should fight until it liberates all of its territory to the 1991 borders (67 percent), indicating that their more somber assessment of the war, no doubt shaped by their personal experiences, did not translate into acceptance of more limited war aims.

“Support” for Negotiations Is Complicated

On the surface, it may seem that a large share of Ukrainians are willing to negotiate with Russia; the Carnegie-sponsored poll found that 43 percent of respondents were in favor when asked a simple yes or no question. Other polls appear to show that Ukrainians have warmed to the idea of negotiations in the past year.

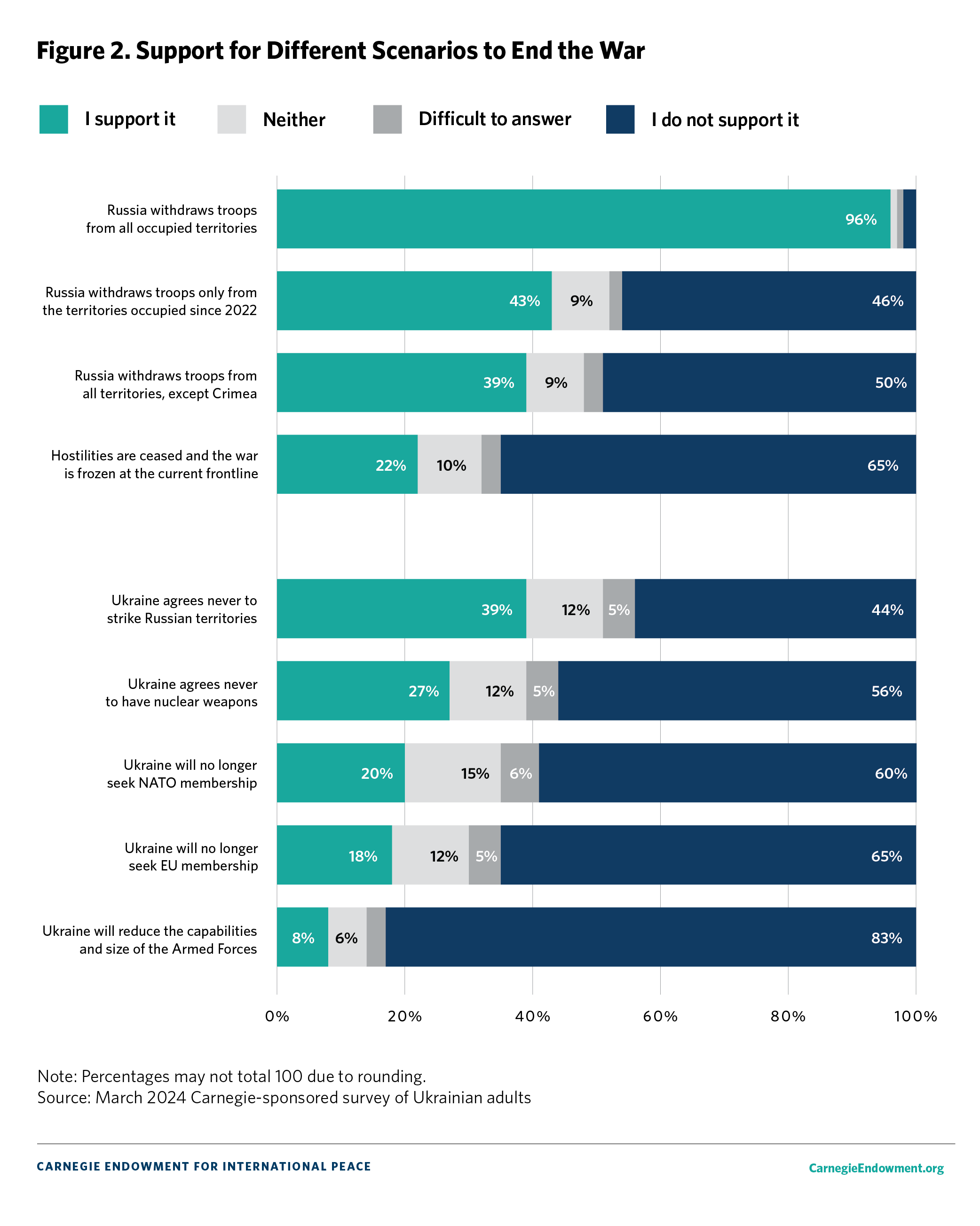

But further analysis and more targeted questioning shows that support for negotiations is largely theoretical. The share of Ukrainians who preferred seeking a compromise to end the war through negotiations fell from 43 percent in the yes or no question to 26 percent when respondents were asked to choose between negotiating with Russia and continuing to fight. Most Ukrainians who expressed openness to negotiate appeared to envision a scenario in which Kyiv was in a favorable enough position to demand the full withdrawal of Russian troops from Ukrainian territory, the prosecution of Russian officials for war crimes, reparations, and other conditions that are nonstarters for the Kremlin.

Asking Ukrainians about various war termination scenarios showed the divergence between their views and Russian demands (see figure 2). Most Ukrainians (83 percent) strongly opposed reducing Ukrainian military capabilities as a condition to end the war—one of the main sticking points in the Russia-Ukraine talks that took place in Belarus and Türkiye in the spring of 2022. Majorities or pluralities also opposed ending the war in the following scenarios: a ceasefire that freezes the current front lines (65 percent), a Ukrainian renunciation of possible EU or NATO membership (65 percent and 60 percent, respectively), a Russian withdrawal from the territories it has occupied since 2022 only (46 percent), or an agreement that Ukraine will never again strike Russia (44 percent).

Support for negotiations is often wrongly interpreted either as an indicator of willingness to accept Russian demands or as a lack of support for the war effort. However, support for negotiations does not contradict the Ukrainian government stance; various Ukrainian officials—most recently, the deputy chief of the Main Directorate of Intelligence of the Ministry of Defense, Vadym Skibitsky—have acknowledged that the war will not be won “on the battlefield alone” and that talks will be necessary eventually, but only when Ukraine is in a position to secure a just and lasting peace.

Many Ukrainians may be open to negotiations in theory, but they overwhelmingly did not trust Russia to negotiate in good faith. Most Ukrainians (86 percent) believed that there is a medium or high risk that Russia will attack again even if there is a signed peace treaty, and even more (91 percent) believed that Russia’s motive to enter negotiations is to take time to prepare for a new attack. Even among those who supported negotiations with Russia, only 21 percent believed that signing a peace treaty would help Ukraine deter future Russian aggression.

Ukraine’s leaders are not wrong to worry about social unrest if the country is forced to sign a disadvantageous peace deal. More than half of respondents said they would join a peaceful protest if they disagreed with the terms of a hypothetical peace treaty. A small but notable minority, 7 percent, said they would join an armed protest; this figure grew to 15 percent among active-duty soldiers and veterans. Of the 71 percent of respondents who said they would demand a change of leadership if they disagreed with the treaty terms, nearly three-quarters said they would do so only when it is possible to hold elections.

Linguistic and regional identities slightly influenced Ukrainians’ attitudes on these issues, with self-identified Russian speakers and residents of eastern and southern Ukraine having marginally more positive views of negotiations and more charitable views of Russia’s motivations to negotiate. For example, among Russian speakers, 56 percent believed Ukraine should negotiate with Russia to achieve peace and 14 percent believed that Russia’s motive to enter into negotiations would be to achieve peace and stop the war (compared to 40 percent and 3 percent of Ukrainian speakers, respectively). But traditional linguistic and regional divides in Ukraine have been narrowing ever since Russia annexed Crimea in 2014 and certainly since the start of the full-scale war.

Ukrainians Want Self-Reliance

Ukrainians value the support they receive from their foreign partners, and a majority believes that this support will either grow or be maintained at current levels over the next couple of years. But most Ukrainians do not expect their partners to fight on their behalf. When asked about what security guarantees Ukraine’s partners should provide, 63 percent wanted long-range weapons, training, and defense industrial support, compared to only 26 percent who wanted partners to deploy their troops to defend Ukraine. These preferences reflect Ukrainians’ understanding of how far allies are willing to go in their support; in other words, it is not that the majority of Ukrainians were against partners deploying troops on their behalf but that they did not believe it would happen.

This realism is also seen in Ukrainians’ views of NATO membership. When asked in a multiple-choice question what steps Ukraine could take to deter future Russian aggression, many more respondents (61 percent) opted for “building a vibrant defense industrial base” than for “joining NATO” (36 percent), signaling Ukrainian society’s focus on self-sufficiency. These views are probably shaped in large part by Ukrainian expectations: most (59 percent) did not expect to see an invitation to join the alliance at the upcoming NATO summit in Washington this July. A similar poll in November 2022 found that Ukrainians were far more likely to choose NATO membership among a set of options to deter Russia, suggesting that Ukrainians are becoming less attached to the idea that their country could quickly join the alliance as a way to end the war.

Only 33 percent of respondents believed that Ukraine should continue trying to receive a NATO invitation in future years if Ukraine does not receive an invitation at this year’s summit. But this figure should be interpreted with some caution. It may reflect a tactical preference—not asking for what cannot be achieved at the moment—rather than a desire to forgo NATO membership entirely. Indeed, only 20 percent of respondents said they would accept Ukraine no longer seeking membership in the alliance as a concession to Russia to end the war.

Ukrainians’ desire for self-reliance is also seen in their views on reacquiring nuclear weapons: 47 percent believed that Ukraine should reacquire them now, and a further 33 percent believed that it should do so under certain circumstances. These figures are theoretical, as there is no evidence that Ukraine’s leaders are pursuing nuclear rearmament. But they show a deep Ukrainian grievance over the Budapest Memorandum of 1994, in which Ukraine received nonbinding security assurances from the United States, United Kingdom, and Russia in exchange for parting with the nuclear arsenal it inherited from the Soviet Union.

Dissatisfaction With Leadership Rising, but Little Support for Elections

Zelensky’s official presidential term expired in late May, but elections are indefinitely on hold while martial law remains in force. While most Ukrainians (63 percent) were at least somewhat satisfied with his performance as president, support for him is unquestionably lower than it was in the initial stages of the war. This was to be expected, as Zelensky’s ratings skyrocketed with the wave of patriotism brought on by the start of the full-scale invasion. His popularity has now come down to approximately what it was shortly after his election in 2019 and remains significantly higher than it was shortly before February 2022.

Only 24 percent of respondents said that elections should be held this year, regardless of whether the war ends by that time; this figure was higher among younger Ukrainians than among the older generations. Even among those dissatisfied with Zelensky’s performance, fewer than half supported holding elections this year. In other words, the president’s sagging popularity does not equate to a popular demand for elections: indeed, many Ukrainians appear to agree with the arguments put forward by Ukrainian civil society leaders and international elections experts that a free and fair vote is impossible given the high risk of Russian attacks on polling stations and other efforts to disrupt the process.

Far worse are assessments of the Verkhovna Rada: only 13 percent of Ukrainians are even somewhat satisfied with the legislative body. This is far from unusual in Ukrainian politics; approval ratings for the Rada have historically been low over the past decade. The overwhelming dissatisfaction with the current Rada is particularly unsurprising given its growing dysfunction, perhaps best evidenced by the arduous process of passing a new law on mobilization.

Further mobilization is often portrayed as a highly unpopular and politically risky decision, but that impression may be exaggerated: 58 percent of respondents supported further mobilization. (This does not necessarily mean that they would be willing to be mobilized themselves.) In other recent polls, higher percentages of respondents agreed that mobilization was needed, as long as it is fair and well-organized.

Ukrainians are becoming attuned to the manpower challenge they face and the fact that mobilization is a necessary step to address it. Still, Zelensky faces some political peril in moving forward on mobilization because of lingering societal concerns about the process. At the time the poll was conducted, the draft law on mobilization included points on demobilization, which would have allowed exhausted units at the front to be rotated. These points were removed from the draft law before it finally passed in April, to public disappointment. Moreover, ongoing corruption scandals associated with the military recruitment system have dented many Ukrainians’ faith in the process.

Some experts have posited that veterans and active-duty service members will play a larger role in domestic politics after the war. The drawn-out process of General Valery Zaluzhny’s dismissal as commander-in-chief of the Ukrainian Armed Forces in early 2024 fueled these arguments, as his potential to run for president in a future election was allegedly a factor in Zelensky’s decision to dismiss him. But when asked about the most important quality in Ukraine’s next leader, few respondents (9 percent) chose military experience. Far more respondents placed a priority on a candidate’s ability to heal the nation (29 percent), commitment to fighting corruption (24 percent), and economic experience (19 percent). Other surveys have shown that many more Ukrainians expect a new political force to emerge from the military environment than from other parts of society, almost certainly because the military and veterans enjoy the overwhelming trust of the Ukrainian public.

Conclusion

Ukrainians remain committed to the war effort, are opposed to capitulating to Russian demands, and are far from clamoring for a change in leadership. They also understand the importance of self-reliance in Ukraine’s long-term defense strategy. Still, their expectations for victory remain high. Ukrainian and Western leaders would be wise to communicate clearly about what is achievable on the battlefield and under what circumstances a more intensified diplomatic process could meaningfully pave the way for a just and lasting peace.

AUTHORS

- Nicole GonikJames C. Gaither Junior Fellow, Russia and Eurasia Program

- Eric CiaramellaSenior Fellow, Russia and Eurasia Program