Ceci est un extrait de la dernière note de Bill Gross, le plus célèbre et l’ex plus gros gérant obligataire du monde.

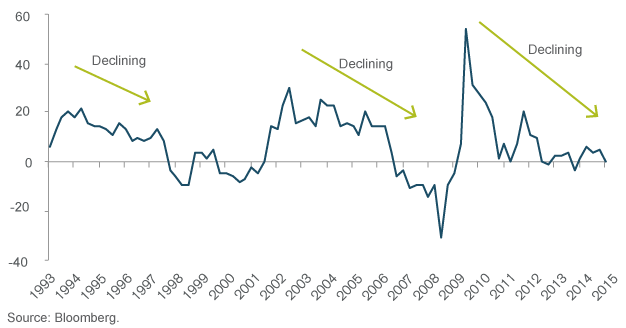

Historically, central banks have comfortably relied on a model which dictates that lower and lower yields will stimulate aggregate demand and, in the case of financial markets, drive asset prices up and purchases outward on the risk spectrum as investors seek to maintain higher returns. Today, near zero policy rates and in some cases negative sovereign yields have succeeded in driving asset markets higher and keeping real developed economies afloat. But now, after nearly six years of such policies producing only anemic real and nominal GDP growth, and – importantly – declining corporate profit growth as shown in Chart 1, it is appropriate to question not only the effectiveness of these historical conceptual models, but entertain the increasing probability that they may, counterintuitively, be hazardous to an economy’s health.

Après plus de 6 ans de taux nuls d’intérêt nuls ou négatifs, les politiques monétaires ne produisent plus que des résultats décevants: croissance réelle anémique et déclin des profits des entreprises. Il est temps de s’interroger sur l’efficacité de ces politiques et les risques qu’elles font courir à nos économies.

The proposed Gresham’s corollary is not just another name for “pushing on a string” or a “liquidity trap”. Both of these concepts depend significantly on the perception of increasing risk in credit markets which in turn reduce the incentive for lenders to expand credit. But rates at the zero bound do much the same thing. Zero-bound money – quality aside – lowers incentives to expand loans and create credit growth.

Les taux lorsqu’ils sont quasi nuls réduisent l’incitation des prêteurs à prêter plus et à créer du crédit.

Will Rogers once humorously said in the Depression thathe was more concerned about the return of his money than the return on his money. His simple expression was another way of saying that from a system wide perspective, when the return on money becomes close to zero in nominal terms and substantially negative in real terms, then normal functionality may break down.

Quand les taux sont proches de zéro, alors le système finit par ne plus fonctionner normalement.

If at the same time, and over a several year timeframe, bond investors become increasingly convinced that policy rates will remain close to 0% for an “extended period of time”, then yield curves flatten; 5, 10, and 30 year bonds move lower in yield, which at first blush would seem to be positive for economic expansion (reducing mortgage rates and such). It would seem that lower borrowing costs in historical logic should cause companies and households to borrow and spend more. The post-Lehman experience, as well as the lost decades of Japan, however, show that they may not, if these longer term yields are close to the zero bound.

Les réactions attendues ne se produisent pas, et ce qui intuitivement devrait être positif pour les économies cesse de l’être: les entreprises et les particuliers n’empruntent pas et ne dépensent pas plus .

Graphique de la croissance des profits aux USA de 1993 à 2015

In the case of low yielding sovereign, as well as corporate AAA and AA rated bonds, this new Gresham’s corollary is certainly counterintuitive. If a government or a too big to fail government bank can borrow near 0%, then theoretically it should have no problem making a profit or increasing real economic growth. What is more important, however, is the flatness of the yield curve and its effect on lending across all credit markets. Capitalism would not work well if Fed Funds and 30-year Treasuries co-existed at the same yield, nor if commercial paper and 30- year corporates did as well.

A priori si on peut emprunter à 30 ans sans intérêt, il devrait être facile de réaliser des profits et d’accélérer la croissance économique et pourtant ce n’est pas ce que l’on voit. Le capitalisme ne marche pas si les taux au jour le jour et les taux à 30 ans sont les mêmes, pour que cela marche il faut que la courbe des taux en fonction de la durée soit pentue.

Investors would have no incentive to invest long term. What central bank historical models fail to recognize is that over the past 25 years, capitalism has increasingly morphed into a finance dominated as opposed to a goods and service producing system.

Dans ce systeme de taux zero les capitalistes n’ont aucun intérêt à investir à long terme. Les modèles des Banques Centrales n’ont pas intégré le fait que depuis 25 ans le capitalisme a muté, il est dominé par la finance et ceci est le contraire d’un système fondé sur la production de biens et de services.

It is not only excessive debt levels, insolvency and liquidity trap considerations, then, that delever both financial and real economic growth, it is the zero-bound nominal policy rate, the assumption that it will stay there for “an extended period of time” and the resultant flatness of yield curves which may be culpable. As a result, in the case of banks, their “Nims” or net interest margins are narrowed as Chart 1 suggests. It stands to reason that when bank/finance profit margins resulting from maturity extension are squeezed (curve flattening) then overall corporate profits are squeezed as well.

La cause de cette situation n’est pas seulement le niveau excessif des dettes, c’est également le fait que l’on proclame que cela va durer très longtemps et le fait que les courbes de taux soient plates. Les marges nettes des banques procurées par la transformation sont réduites et minuscules, elles sont squeezées et tous les profits des entreprises sont également squeezés eux aussi.

This new Gresham’s corollary applies to other finance based business models as well. If long term liability based pension funds and insurance companies cannot earn an acceptable “spread” from maturity extension – and in the case of zero based policy rates – cannot therefore earn an acceptable return on their investments to cover future liabilities, then capitalism stalls or goes in reverse. Profit growth or profits themselves come down and economic growth resembles the anemic experience of Japan; pension funds begin to cut benefit payments as recently threatened in Puerto Rico and Illinois, reducing disposable personal income.

Ce raisonnement s’applique à toutes les institutions qui fonctionnent selon le modèle financier comme les assurances et les retraites. Si elles ne peuvent gagner un profit raisonnable par l’extension des maturités, en employant « long », elles ne peuvent remplir leur fonction. La croissance des profits disparait, voire même les profits eux même chutent, la croissance économique devient anémique comme au Japon.

…..

Individual households must also save more and consume less if the return on their savings is reduced by a flatter yield curve.

Les ménages également sont victimes de ce sytème car ils doivent économiser plus et consommer moins puisque le rendement de leur épargne est réduit par une courbe des taux plate.

My primary thesis, supported by the above examples, remains that capitalism does not function well, and profit growth is stunted, if short term and long term yields near the zero bound are low and the yield curve inappropriately flat.

Ma thèse est que le capitalisme ne fonctionne pas bien et que la croissance des profits est empêchée si les taux longs et courts sont proches de zéro et que la courbe des taux est plate.

Merci de traduire ce texte car le sabir anglo/financier n’est pas forcément évident

en France. (les textes en angliche ne provoquent guère de commentaires…).

On comprend mieux l’impasse structurelle et récessive où s’est enfermé la finance,

(sans parler des autres causes).

Concernant les dépenses des ménages, il faut quand même souligner la faible

rémunération, depuis longtemps, de l’épargne populaire, le plus souvent inférieure

à l’inflation réelle.

J’aimeJ’aime